This week, in honor of Youth Art Month, we will be hearing from Gina Moreland, Executive Director of Habitot Children’s Museum in Berkeley, California. The mission of Habitot Children’s Museum is ”to help the broad community of parents and caregivers raise curious, creative and confident children.” Underlying the Museum’s mission is the knowledge that, in the earliest years of life, when brain development is advancing rapidly, intellectual stimulation and parent involvement are crucially important. Habitot’s Art Studio provides a place where children can express themselves creatively through art. Here’s what Gina had to say…

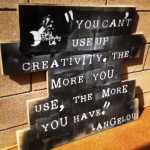

The great modern artist, Pablo Picasso, famously said, “It has taken me a lifetime to learn how to paint like a child.” The uninhibited and completely creative art of very young children is always in evidence in the Art Studio at Habitot Children’s Museum. Over the past 17 years, tens of thousands of young children, age 0-5, have explored a wide range of art materials and art-making at Habitot – often for the first time. Art Studio Coordinator Nora Garcia, who develops curriculum for the Studio, often says, ”this is where artists are born.”

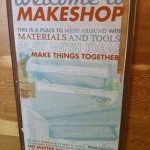

Far too many settings for young children provide what we call ‘school-art’ or seasonal projects where there is one right way to do a project. By contrast, Habitot’s art experiences are open-ended and allow a child to express him or herself with the provided materials, which is what true art is. A giant Lucite sheet is mounted on the wall at one end of the Art Studio. Here, children have an enormous canvas for drawing and painting – and often, several children will work on the wall at once. When they’ve finished, the wall can be wiped down for the next child. “The emphasis is on the art experience, not necessarily the final product,” says Nora. The shifting kaleidoscope of colors on the wall are endlessly fascinating to adults.

Each year, Habitot presents a Contemporary Art Show to the community with works created in the Art Studio. Invariably, the framed works draw attention and viewers are always surprised to find out they were painted by a child under 5. Some sell for $100 or more. Habitot has plans to relocate the museum to a larger and more accessible building in the next few years so that it can better serve its annual audience of 65,000.

Cloudberry Studio will be leading the Habitot team through the Master Plan and Concept Design, that includes an expansion of the Art Studio.

From my friend Sharon: “…I talk about how the sound of the room overwhelms Caleb; how people’s voices echo if the ceilings are really high, how employees interact with us, if there’s music playing in a foyer…we never ever take an elevator anywhere, so we’re very fond of carpeted stairwells because the carpet absorbs the noise of clanking steps and squeaky doors.” (Sharons blog:

From my friend Sharon: “…I talk about how the sound of the room overwhelms Caleb; how people’s voices echo if the ceilings are really high, how employees interact with us, if there’s music playing in a foyer…we never ever take an elevator anywhere, so we’re very fond of carpeted stairwells because the carpet absorbs the noise of clanking steps and squeaky doors.” (Sharons blog:  From my friend Grace: “…every kid with autism is different! For us too, our major challenge is often loud noises. Interactive play is enjoyed but not if it requires working with other children. For us, drawing is a great way to interact with an exhibit. Our local art museum has a room for children and Elijah loves it, there’s freedom to move around the different centers at will (or skip the ones he doesn’t feel comfortable with), and there’s also a place to try out the same types of art currently on exhibit. (Grace’s blog is here:

From my friend Grace: “…every kid with autism is different! For us too, our major challenge is often loud noises. Interactive play is enjoyed but not if it requires working with other children. For us, drawing is a great way to interact with an exhibit. Our local art museum has a room for children and Elijah loves it, there’s freedom to move around the different centers at will (or skip the ones he doesn’t feel comfortable with), and there’s also a place to try out the same types of art currently on exhibit. (Grace’s blog is here: